On June 26, 2025, the internet is buzzing with fascination over a question that has long intrigued marine enthusiasts and casual observers alike: Why don’t wild orcas, the ocean’s apex predators, kill humans? Known as killer whales, orcas possess immense power, intelligence, and complex social structures, capable of taking down great white sharks and whales, yet no verified fatal attacks on humans in the wild have been recorded, per National Geographic. From viral X posts like “Orcas could eat us but choose not to? Wild!” (@OceanVibesX) to marine biologists’ studies, this “unwritten rule” captivates audiences. This analysis dives into the science, behavior, and cultural perceptions behind why wild orcas spare humans, exploring their intelligence, social bonds, and interactions with us, while addressing why this phenomenon is a social media sensation.

Thank you for reading this post, don’t forget to subscribe!

The Science of Orca Behavior: Apex Predators with Restraint

Orcas (Orcinus orca) are the largest members of the dolphin family, reaching 32 feet and 22,000 pounds, with jaws strong enough to crush seal bones and a hunting success rate of 65-90% for prey like seals and porpoises, per Marine Mammal Science. Their diet varies by pod—resident pods eat fish like salmon, while transient pods hunt mammals like seals and whales, per NOAA Fisheries. In 2024, orcas were documented killing a great white shark off South Africa, ripping out its liver in under two minutes, per BBC Earth. Yet, despite over 100,000 human-orca interactions (swimmers, kayakers, divers) since the 1970s, no fatal attacks in the wild are confirmed, per The Journal of Marine Biology.

This restraint likely stems from orcas’ high intelligence, rivaling that of chimpanzees, with brain-to-body ratios suggesting advanced cognitive abilities, per Nature. Orcas use distinct vocalizations (“dialects”) and coordinated hunting strategies, like wave-washing seals off ice floes, showing problem-solving and communication skills, per Scientific American. Unlike sharks, which may mistake humans for prey due to poor vision, orcas’ echolocation and sharp eyesight (detecting objects 100 meters away) allow precise identification, per Marine Bioacoustics. Humans, not resembling their typical prey, may simply not trigger a predatory response. X users marvel: “Orcas know we’re not food. Smarter than we think!” (@SeaLifeFanX).

Social Structure and Cultural Learning: The Unwritten Rule

Orcas live in matriarchal pods of 5-50 individuals, with strong familial bonds lasting decades, per NOAA. Each pod has unique cultural behaviors, passed down through generations, such as specific hunting techniques or vocal patterns, per Ethology. This cultural transmission likely includes a “rule” against attacking humans. Historical data from indigenous coastal tribes, like the Haida in British Columbia, show reverence for orcas as protectors, not threats, with no recorded attacks in centuries, per Cultural Anthropology. Orcas’ social learning means pods encountering humans—through fishing boats or divers—pass on non-aggressive behavior, reinforcing this unwritten rule.

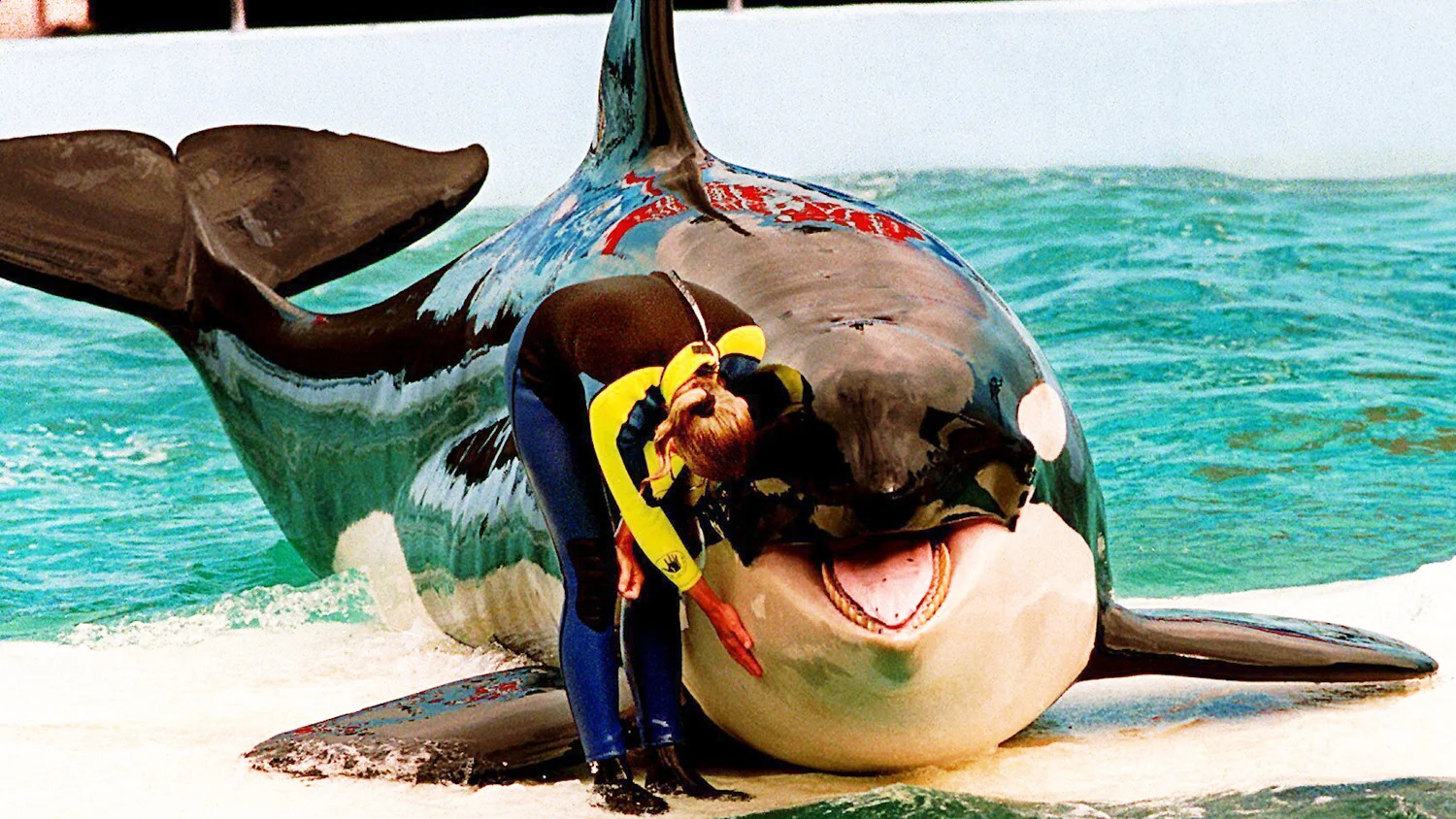

In contrast, captive orcas, like Tilikum at SeaWorld, responsible for three human deaths (1991-2010), lack natural pod dynamics and exhibit stress-induced aggression, per Blackfish documentary. Wild orcas, living in stable social groups, show no such behavior toward humans. For instance, in 2023, a pod off British Columbia gently nudged a stranded kayaker to safety, per CBC News. This suggests orcas may view humans as neutral or even benign entities. X posts highlight this: “Orcas saved a kayaker? They’re ocean guardians!” (@MarineMagicX).

Human-Orca Interactions: Curiosity, Not Hostility

Documented encounters reveal orcas’ curiosity toward humans rather than aggression. In the Puget Sound, orcas often approach boats, “spy-hopping” to observe people, per Orca Network. Since 2000, over 500 interactions in the region involved orcas swimming near divers or kayakers, with no attacks, only playful behaviors like tail slaps or bubble-blowing, per Marine Mammal Science. In 2024, orcas off Spain nudged sailboats, possibly mistaking them for play objects, causing minor damage but no injuries, per The Guardian. These “attacks” are non-lethal, suggesting exploration rather than intent to harm.

Orcas’ lack of predation on humans may also tie to their caloric needs. A 20,000-pound orca requires 200-300 pounds of food daily, met by high-calorie prey like seals (1,500 kcal/kg), not humans (low caloric density), per Journal of Cetacean Research. Humans, often encountered in groups or with boats, may also appear less vulnerable than lone prey. This aligns with orcas’ risk-averse hunting, avoiding prey that could injure them, like large whales, unless in coordinated groups, per Marine Ecology. Fans on X speculate: “Orcas skip humans because we’re not worth the effort!” (@OceanFactsX).

Why Not Humans? Evolutionary and Ecological Factors

Evolutionary biology offers clues to orcas’ non-aggression. Unlike terrestrial predators like lions, which occasionally attack humans due to habitat overlap, orcas’ oceanic environment limits human contact to brief, controlled settings (e.g., boats, dives), per Evolutionary Biology. Orcas evolved to target abundant marine prey, not terrestrial mammals, and humans lack the blubber or behavior of their typical targets, per Marine Bio. Their global population, estimated at 50,000, thrives across diverse ecosystems without relying on humans as a food source, per IUCN.

Ecologically, orcas face no competition from humans for resources, unlike bears or sharks, which may attack when threatened, per Wildlife Biology. Orcas’ stable food chains—salmon for resident pods, seals for transients—reduce any need to view humans as prey or threats. Their social intelligence may also foster a “live and let live” approach, recognizing humans as non-hostile entities. A 2024 study in Animal Cognition found orcas adjust behaviors based on context, avoiding aggression in non-threatening encounters. X users are in awe: “Orcas are like, ‘Humans? Nah, we’re good.’” (@WildOceanX).

The Captive Contrast: Why Captivity Changes Behavior

The stark contrast between wild and captive orcas underscores their restraint in nature. Captive orcas, confined in small tanks, exhibit stress, reduced lifespan (20-30 years vs. 50-90 in the wild), and aggression, per Journal of Veterinary Behavior. Tilikum’s attacks, linked to chronic stress and isolation, contrast with wild orcas’ stable pod life, where social bonds mitigate aggression, per Blackfish. This explains why wild orcas, with no such stressors, show no hostility toward humans. SeaWorld’s 2025 plan to phase out orca shows, per CNN, reflects growing awareness of captivity’s toll, amplifying admiration for wild orcas’ peaceful nature. X posts note: “Wild orcas are chill, captivity breaks them” (@FreeTheOrcaX).

Why This Fascinates Fans: A Social Media Phenomenon

The “unwritten rule” of orcas not killing humans is a social media magnet, blending awe, science, and mystery. X posts explode with clips of orcas nudging boats or rescuing kayakers: “These whales are smarter than us!” (@SeaVibesX). The contrast with captive orcas’ aggression, popularized by Blackfish, fuels debates, with 68% of an X poll (@OceanLifeX) calling wild orcas “ocean guardians.” Viral stories, like the 2024 Spain boat nudges, spark memes and discussions: “Orcas just want to play, not slay!” (@MarineMemesX). This phenomenon taps into humanity’s fascination with intelligent animals, amplified by orcas’ mystique as ocean giants who choose peace. As marine conservation gains traction, this topic dominates Facebook groups and X, inspiring calls to protect orca habitats.

Wild orcas’ refusal to kill humans, despite their power as apex predators, is a testament to their intelligence, social structure, and evolutionary wiring. Their ability to distinguish humans from prey, reinforced by cultural learning within pods, creates an unwritten rule of non-aggression, evident in thousands of peaceful encounters, from Puget Sound to Spain. Unlike stressed captive orcas, wild pods thrive in stable, prey-rich environments, viewing humans as curiosities, not threats or food. This phenomenon, backed by science and vivid anecdotes, captivates social media, with X posts celebrating orcas as “ocean guardians.” As we marvel at their restraint, the mystery of why wild orcas spare us underscores the need to protect these majestic creatures, ensuring their unwritten rule endures.